The Battle of Lake Erie

“the most important day of my life” - Oliver Hazard Perry

For the ships built at Erie, few moments were more important in their story than that of the 10th of September, 1813. The entirety of the month prior to the Battle of Lake Erie Perry had spent searching for the British squadron. Now, in early September, he knew Barclay, the British commander, was hurriedly struggling to complete his own largest ship, Detroit, at Amherstburg on the Detroit River.

Perry set up a base at Put-In-Bay, the only good anchorage from which he could watch for a meeting with the enemy. The British were extremely short of food, and either had to re-supply or be forced to retreat from Detroit and southern Ontario. They could not get through with supply ships until the U.S. squadron had been defeated. If they waited, hunger alone would defeat them.

Barclay needed the battle as soon as possible, even though his crews had even fewer experienced men than Perry’s. His largest ship, HMS Detroit, was being rigged and armed immediately before the battle. This meant her crew had no chance to drill or become familiar with the ship. Perry had at least had a month and a half to get his men into shape.

At dawn on Sep. 10, Barclay’s squadron was sighted approaching Put-In-Bay. Within minutes, the U.S. squadron was making sail and weighing (raising) anchor to meet them. Initially, the wind was southwest, and Perry’s ships spent some time tacking back and forth between Rattlesnake Island and South Bass Island. They could not make enough ground to windward to beat out, and Perry had just ordered the ships to run to leeward of Rattlesnake Island when the wind shifted toward the southeast and enabled them to keep to weather of Barclay.

Barclay went about and formed his line on the port tack, heading west. This gave him more searoom and would keep Perry from getting between him and his base. Perry also formed a line on port tack and stood toward the British line. His own line was planned to oppose his two largest ships, Lawrence and Niagara, against Barclay’s two biggest, Detroit and Queen Charlotte. The U.S. squadron numbered 9 vessels to the British 6, but nearly all the power of both squadrons was in their 2 largest ships, the rest being small vessels with only a few guns each. In terms of total number of guns, the two fleets were fairly evenly matched. However, the heavier weight of shot of the short-range U.S. carronades gave Perry a great advantage in close-range gunnery. The broadside weight was about 150% of the British. In terms of manning, the U.S. had an even more significant advantage. While the numbers of men were similar, 532 for Perry and a few more for Barclay, a much higher proportion of Perry’s men were regular US Navy. The odds were very much in favor of the U.S.

Image courtesy of Peter Rindlisbacher

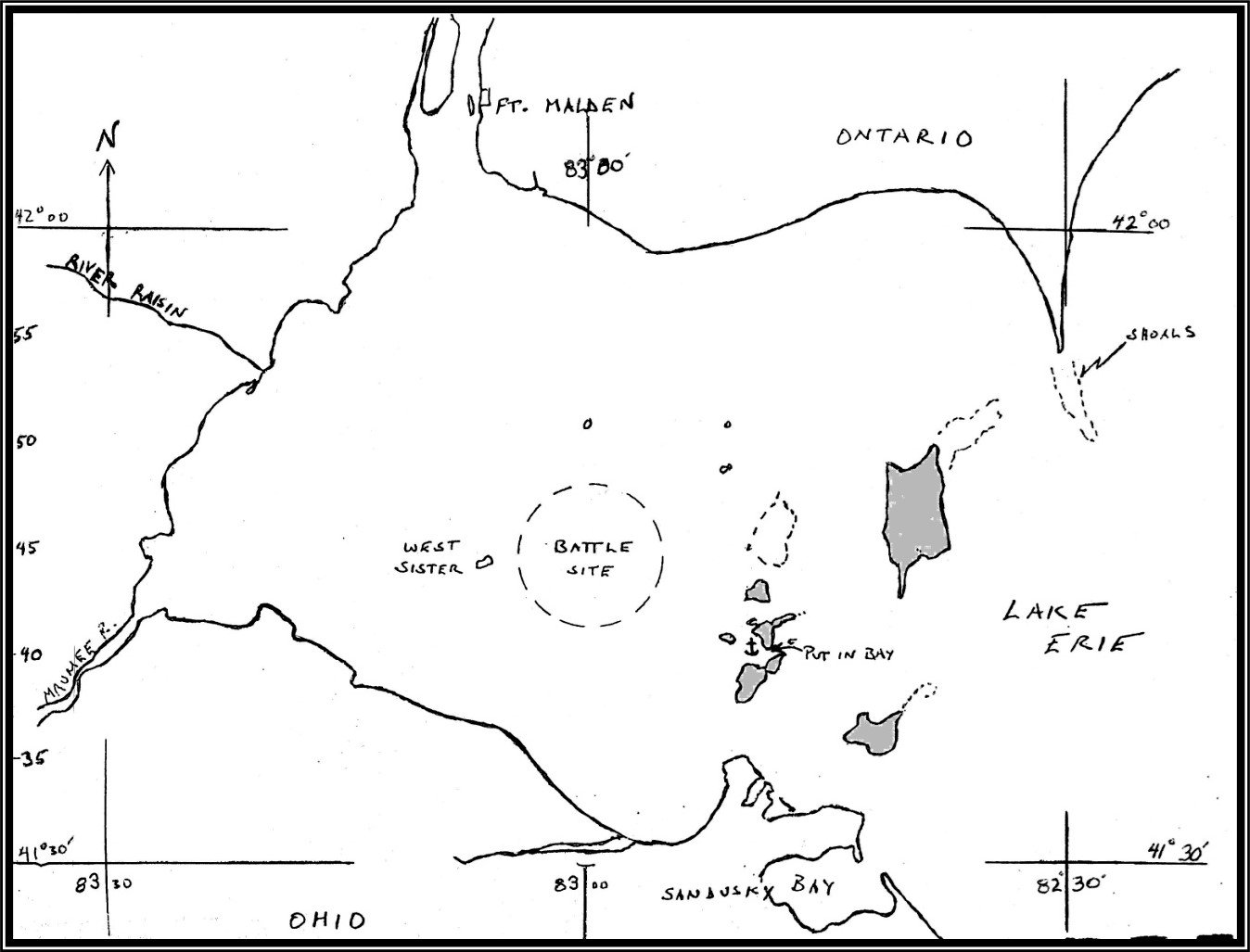

Battle Site - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

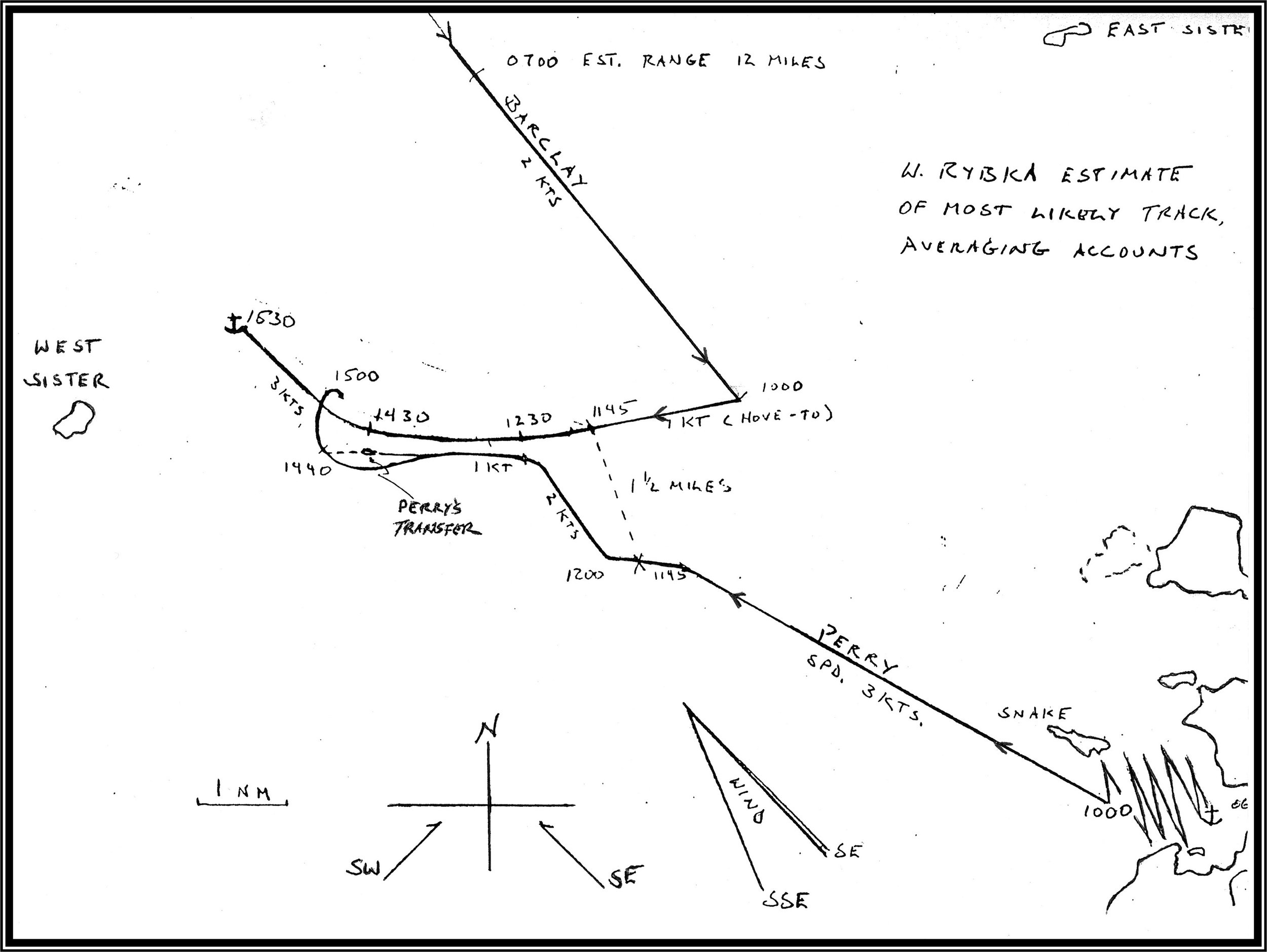

Sailing Paths - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

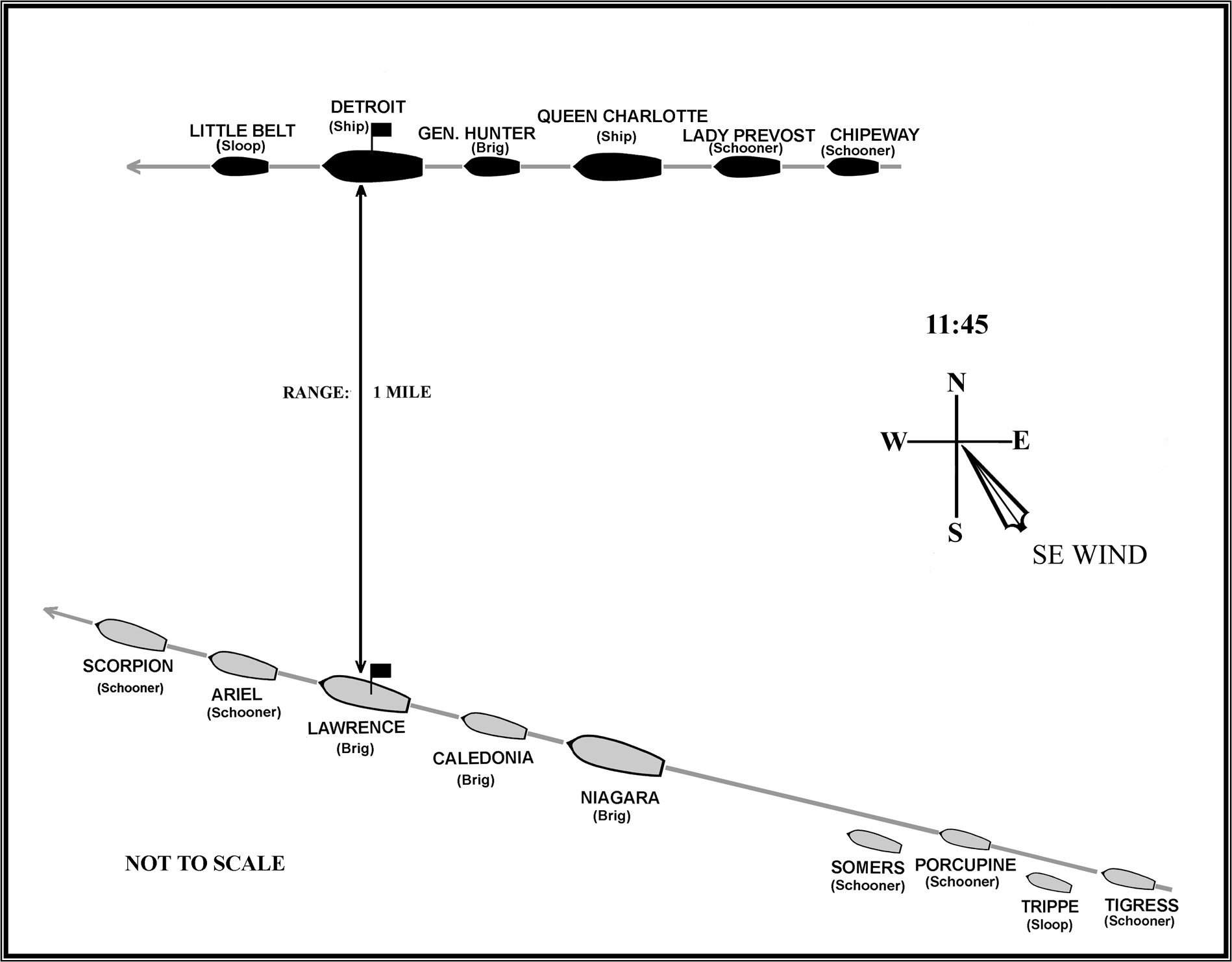

Line of Battle - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

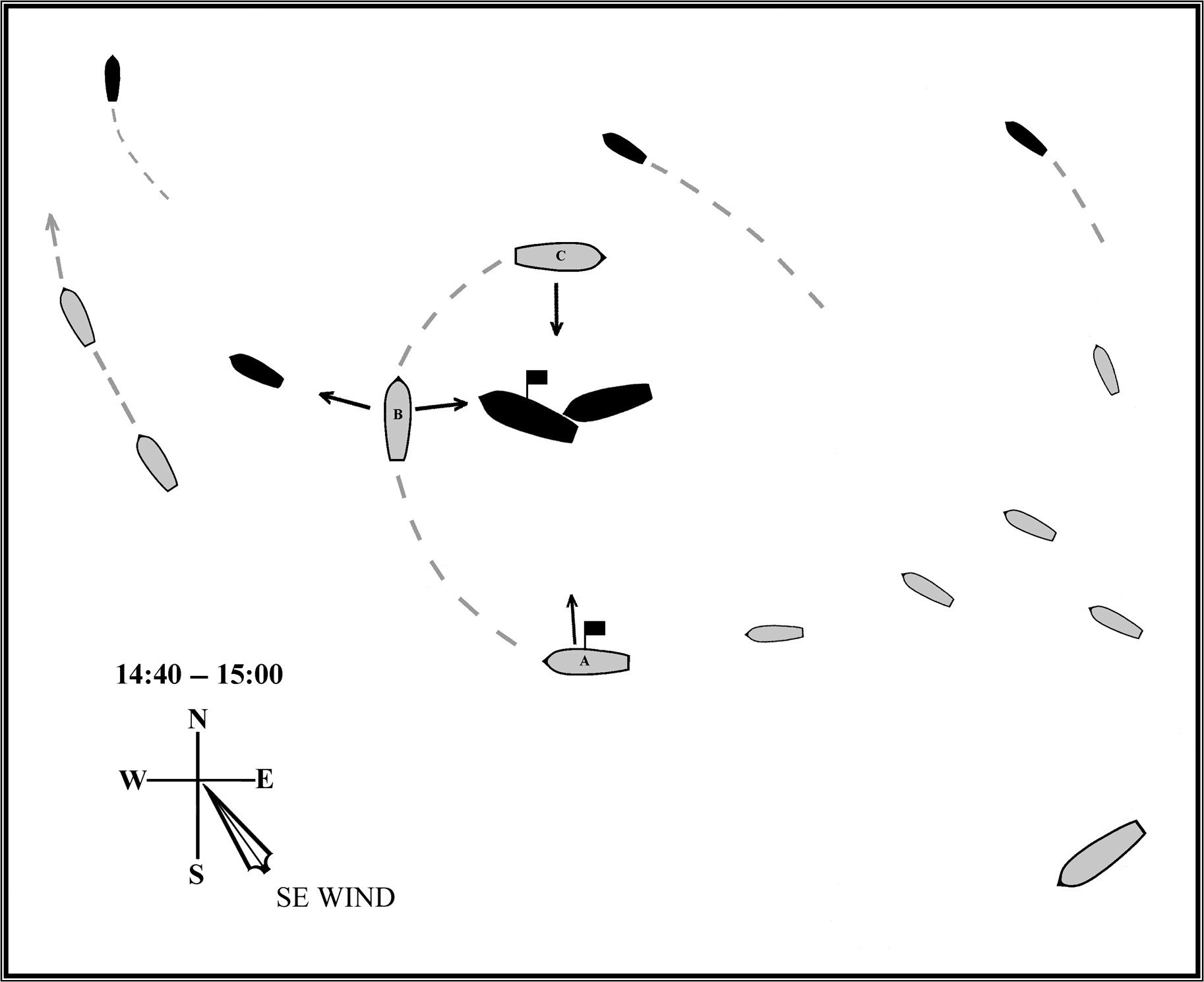

12:30 - 2:30 pm - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

Transferring the Colors - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

Crossing the "T" - Courtesy of Walter Rybka

Barclay had an initial advantage in that his armament was chiefly in long guns which outranged Perry’s carronades, even though Perry could throw a heavier broadside once in range.

The British did a good job of station keeping; their compact line made for mutual support, but this is also simpler to do when awaiting attack from the lee gage position. The wind was now from the south, although extremely light; and Perry was running down towards the British. This made the differing sailing abilities of his ships more noticeable, as well as forcing him to present his bows to the enemy and endure fire before his broadside could be brought to bear. Perry’s orders were to stay close to the Lawrence, close to the enemy, and in line. For reasons never fully explained, Elliott kept Niagara back, nearly out of range. Elliot’s defense was that his orders were to keep station behind Caledonia, a small brig in between Lawrence and Niagara, which proved very slow, but this omits the more important functions of supporting the Commander and closing with the enemy.

The battle opened at 11:45 when a British 24lb. ball struck Lawrence. The light breeze meant the ships were moving so slowly that it took Perry the next 45 minutes to close the range from about a mile down to the 200 yards or so at which range carronades were most lethal. During all this time Lawrence continued to receive fire she could not answer except with the 2 long 12-pounders. By 12: 30 Perry was able to open fire in earnest. Because Elliott failed to close, Perry found himself under fire from both the large British ships and a smaller brig as well. The concentration of force at this point was completely with the British. The result of this situation was that for the next two hours, Lawrence fought an artillery duel on very uneven terms. While her own 32 lb. carronades were inflicting great damage on the British, the combined weight of fire of Detroit, Hunter, and Queen Charlotte eventually put all of Lawrence’s guns on the engaged side out of action. Eighty percent of the men fit for duty on Lawrence were casualties, 22 killed and 66 wounded, a proportional toll seldom exceeded in the age of sail.

Perry had the great good luck to remain uninjured while his ship became a shattered slaughterhouse around him. With both guns and crew gone, there was nothing more that could be accomplished from the Lawrence. Perry further had the luck that one of the ship’s boats was still intact towing astern. Perry saw that Niagara was still undamaged and determined to continue the fight from her, using the boat to transfer. Perry turned over Lawrence to Lt. Yarnall, who later struck the U.S. flag to surrender to avoid further useless slaughter.

Perry’s transfer to the decks of Niagara is perhaps one of the most recognized moments in the Battle of Lake Erie. For many artists, this is the moment they choose to replicate. That said, it was sheer luck that Perry was not only able to survive but, then continue the fight and eventually win the day. Once aboard, Oliver took command from his next in command, Jesse Duncan Elliott, and raised his banner high above the decks of Niagara. In a moment of confusion, the British believed the Americans to be retreating however, they were actually pressing on, taking advantage of the weather gauge (favorable winds). It is here where the two largest vessels in the British squadron, Queen Charlotte and Detroit run into one another, becoming entangled in a mess of rigging. Perry saw the opportunity - a moment to unleash sheer devastation on the unsuspecting British ships. Niagara was ordered to close in and swing into the British line.

“At 45 minutes past two, the signal was made for “closer action”. The Niagara being very little injured, I determined to pass through the Enemy’s line; bore up, and passed ahead of their two Ship and a Brig, giving a raking fire to them from the Starboard guns, and to a large Schooner and Sloop from the Larboard side, at half Pistol shot distance. ”

- O.H. Perry in his after action report

Within 15 minutes of Perry’s transfer, the British squadron surrendered - the Battle of Lake Erie was over. The Americans celebrated victory and were masters of the Lake. The British never again regained control of Lake Erie. It is estimated that there were 123 American casualties (27 deaths) and 440 British (41 deaths). As for Perry, he became a hero overnight. In the evening after the battle, Perry found a pencil and scribbled the following message to William Henry Harrison - Dear General: “We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop.”

The British were unable to put anyone onboard to take her as a prize because all of their boats had been destroyed. Perry’s amazing luck held in that he survived the transfer to Niagara under a storm of British fire. Had he not made it, he may have gone down in history as being killed while fleeing from his ship in defeat.

Upon reaching Niagara, Perry had a short and grim meeting with Elliot. Accounts predictably differ as to the words exchanged. Elliot apparently suggested and Perry accepted that Elliot should go off in the boat to encourage the smaller vessels to close up. The breeze was now freshening enough for them to make better speed in any case, and they were eventually engaged. Immediately after Elliot’s departure, Perry proceeded to sail the fresh Niagara into the British line to closely engage.

By this time, 2:40 p.m., all the senior officers on both Detroit and Queen Charlotte were either dead or had suffered incapacitating wounds. Many of their port guns were also dismounted. Their rigging had been badly shot up as well, rendering them all but uncontrollable. The junior officer in charge of Detroit, on seeing the Niagara bearing down, struggled to wear ship (a 180-degree turn away from the wind) to present his less damaged starboard battery. Queen Charlotte could not due to rig damage, with the result that her headgear fouled the Detroit’s mizzen rigging. The two ships became locked together and were helpless.

Perry’s luck had been crowned by the British catastrophe, which allowed Niagara to cross the T on both British vessels simultaneously. Niagara’s starboard broadside ripped down the length of the already battered enemy vessels while her port broadside wreaked havoc on the Lady Provost. Within fifteen minutes of his transfer, the British surrendered.

Perry returned to his own ship, the Lawrence, to receive the British surrender. Immediately afterward he retired to his cabin for a moment and hurriedly scrawled his famous message to Gen. Harrison

“We have met the enemy and they are our, two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop”

“we have met the enemy and they are our, two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop. After the battle all ships anchored, and the survivors turned to clearing away the wreckage, tending the wounded, and burying the dead. The British practice was to throw the dead overboard as they fell during a battle, only those who fell at the end of a battle received a burial. U.S. practice was to send all casualties below. The dead were sewn into their hammocks, weighted with shot; and a burial ceremony was held after the battle. The dead enlisted men were slid over the side that night. Dead officers from both sides were buried ashore on South Bass Island two days later when all ships returned to that anchorage.

By the standards of the day, the Battle of Lake Erie was a very small action. The combined manpower of all crews of both sides would barely exceed the crew of a single “First Rate” (100 gun Ship of the Line). Many battles had been fought between European fleets numbering twenty to thirty such ships on a side! For the first time, the U.S. Navy had fought a fleet action. In the Barbary wars there had been some action requiring maneuvering a squadron of ships, but these had been shore bombardments, not engagements against moving ships. This also marked the first time that an entire British squadron, however small, had been forced to surrender en masse. Even though the British had been forced by circumstances to seek battle in a very unready condition against a foe whose weight of shot outgunned them, this was still a blow to their pride. Needless to say, it was also a euphoric boost to U.S. morale. The Battle of Lake Erie, by leaving the U.S. in complete control of the Lake, eliminated any chance of the British re-supplying their garrison at Detroit, which in turn forced them to abandon it and retreat to the east.

Perry was next able to use the fleet to transport troops to the north shore of Lake Erie, where they intercepted the retreating British army and defeated them at the Battle of the Thames River (Moraviantown). It was at this battle that the Indian chief Tecumseh was killed. His death, combined with disillusionment with the British, led to the collapse of the Indian confederacy allied with the British. The British were never able to reestablish their power in the West for the rest of the war. In summary, Niagara played a key role in winning the crucial Battle of Lake Erie, which firmly secured the established northern frontier for the U.S. Although the battle had nearly been lost, Perry’s great courage, dogged perseverance, and extreme luck gave the U.S. the victory.